Zou Yaqi: Performing the internet, One Viral Project at a Time

Art, Algorithms, and Intimacy in a Generation That Grew Up Online

Hi,

Reader of new and old! You might be tired by the short fiction posts, after a stint in a self-discovery literary circle, I am back and here is to feature interesting humans. I hope you enjoy reading!

Zou Yaqi, a Chinese self-made performance artist born in 1998, uses the internet not just as a medium, but as material. A media darling, she hits multiple cultural pressure points in China through her viral projects: the widening wealth gap, mother-daughter dynamics, and female self-love. She disrupts the notion of permanence in art and has attracted millions of devoted followers—75% of whom are young women.

Zou studied and worked primarily in China. I’m not sure she counts as a third culture kid by strict geographic definition, but her opposing takes on capitalism and communism (the latter framed as a unified utopia) offer a fascinating read—and reflect the split mindset of many young Chinese today.

Below is a write-up based on an artist interview I conducted for BCAF (Beijing Contemporary Art Foundation). [Here for the original Q&A in Mandarin.]

I. The Anna Delvey of China?

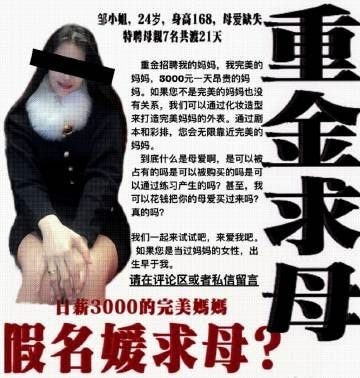

Zou has publicly referenced several artists in her work. One is performance artist Cao Yu, known for provocative acts like photographing public urination and straddling a gushing faucet. Another is Amalia Ulman, the American artist who staged a fake socialite persona on Instagram to critique digital performance culture. Zou’s 21-day Beijing project builds on these “traditions” but takes them further.

In that project, she impersonated a runaway rich girl—Hermès knockoff bag in hand, Vivienne Westwood necklace around her neck—while seeking shelter in upscale spaces. She slept in airport VIP lounges, cosplay bars, 24-hour hotpot chains, and luxury hotel lobbies. The piece went viral, prompting debates about privilege, aesthetics, and access. Renowned artist Chen Danqing praised her style as “spontaneous, autonomous, self-consistent—and natural,” calling it a rare breakthrough in two to three generations of performance art in China.

In one statement, Zou reflected on trying on a priceless Tang Dynasty jade bracelet at an auction. “In that moment, I had it. And in the next, I didn’t,” she said—framing wealth as an illusion, flickering between possession and absence. She titled the work “Instantaneous Ownership.”

The impact of impersonating lingered. Zou later experienced insomnia, anxiety, and awkward conversations with close friends. Yet the project also changed her life: newly graduated from art school, she was quickly signed by an art label, given a monthly stipend, a studio, and production funding.

When I visited her studio for the interview, she moved quickly and spoke even faster. Friendly and apologetic, she seemed constantly in a rush. The bathroom walls were graffitied with characters from Panty & Stocking with Garterbelt, a Japanese anime about two angels—one addicted to sex, the other to sugar—who fight demons on Earth. The door jammed; beside a barely functioning toilet sat perfume bottles, jewelry, and Lolita dresses. It felt like a crash site from the luxury life she once performed.

It’s not quite right to compare Zou to Anna Delvey. Anna conned collectors; Zou is the artist they now collect. Yet both mythologize themselves, play with wealth, and command public attention. In our conversation, Zou quoted Mao and emphasized that the original intent behind her work is “to stand with the people.” Art, she said, has long been a plaything of the rich—and disrupting that to make everyone look more critically online is what drives her.

II. Mothers and Their Daughters

Like Anna, Zou is self-made. She once said her ambition came from rage: growing up in a family that favored her younger brother, she felt the weight of gender-based powerlessness. Becoming a great artist was her way to reclaim value.

Thousands of women online felt seen. They judged the “mothers,” reflected on their own, and marveled at the forms motherly love can take. Others mourned Zou’s desperation to be loved. Yet she’s never spoken to her real mother about the project. When I asked why, her face tightened.

Online, she posts like a melancholic heiress: fur coats, cryptic captions, passenger-seat selfies, messages about missing her three cats. She speaks to fans with maternal warmth, yet shields her own mother from view.

III. Fame, Fans, and Censorship

Her third project turned toward self-love. Participants created AI versions of their ideal selves and went on simulated dates, all directed by Zou. One woman imagined herself as a wild mountain warrior; a post-00er married her ideal self; another took her AI self to a beach date. The series prompted waves of emotional responses from fans—encouraging self-acceptance and sparking a collective mission of learning to love themselves.

Zou says she doesn’t aim to criticize women; she wants to understand them, befriend them. In a TED-style talk, she said, “When people used to ask me what inspired my work, I’d say: the pleasure of sex and love.”

Her fanbase is overwhelmingly female—75%, aged 18 to 35. Comment sections glow with positivity, a rare thing in China’s often hostile online climate. But it’s not all easy. Some fans see her as a sister, others as a savior. Some become angry if she doesn’t meet their emotional needs. Zou disclosed that one fan, disappointed by her, have even threatened self-harm.

Still, she says her greatest challenge is censorship. “It was just this bit of my chest—not even cleavage!” she exclaimed, outlining a small square with her hands. More often, though, it’s the subject matter itself that leads to takedowns. She moderates herself carefully, always calculating how far she can go.

Zou is undeniably a child of the internet. Animated characters once saved her life. She grew up on Bilibili, Douyin—the same platforms where her fans now gather. She considers herself an artist who has mastered public communication. She even enlists friends to leave controversial comments under her videos, to make them “spicier.” In her view, a work of art must circulate like currency—and negative feedback counts too.

“I feel incredible editing these videos,” she told me, eyes sparkling. “Nothing compares to that feeling.”

As she stood up to find me a cup of water, I noticed the back of her dress was only half-buttoned. She was rushing again. I asked if she feels pressure to top her last project. She smiled. “I’ve got five ideas in the bank,” she said. “That’ll get me through another five years.”