welcome to the year of absurdity #tiktokrefugee

documenting the kaleidoscope of reactions in real life, decipher memes and the WALL

Two weeks ago, a digital exodus began. Americans, exiled from TikTok by political bans, found an unlikely refuge: Xiaohongshu, a Chinese social media app. They called themselves #tiktokrefugees. What followed was a kaleidoscope of cultural exchange, misunderstandings, and humor—an absurd yet oddly poignant snapshot of globalized digital culture.

Reactions in real life

Now that the heat has died down, and the ban has temporarily lifted, many people—both American and Chinese—are finally regain their footing. Here’s a deep dive into what exactly happened, presented in chronological order:

My friend A and I, both ex-journalists, scrambled to save screenshots of disappearing posts—PTSD from creating content under watch. She took the adventurous route. She sent me profiles of Mr. Earth, Mr. Bug (Seventeen), and indie bands she loves. Great lesbian content too. She drooled over Inuit slicing salmon in the Arctic and eventually landed on BL (boy love) content, calling it her new home.

B, who returned to China after studying in the U.S., was less optimistic. When I asked if the trend would last, his reply was blunt: “Only if they can make money.”

C, still living in Brooklyn after being pushed out of Manhattan by rising rents, was more analytical. By the end of the first week, the cultural exchange had shifted to life exchanges—health insurance, rent, and grocery prices. Americans in the comments were stunned to learn that China could be more living-friendly. An ER trip in the U.S. costs $1,200, while in China, it’s a fraction of that.

One meme captured it best: this sort of cultural exchange worked better than any Chinese government propaganda.

C chalked it up to class differences. Xiaohongshu originally targeted study-abroad Chinese, mostly women, showcasing their glamorous lifestyles. These users tend to be well-educated, wealthy, and based in China’s top cities. Comparing them to lower-income groups in the U.S. made the disparity stark.

I’m not sure it’s that simple. Xiaohongshu has grown more grassroots—or maybe that’s just my own echo chamber. Sure, it started out with an overly polished vibe, but now you can find almost anything there. For me, it’s a mix of HR, home doctor, and chef. You get real-time, real-person murmurs in China.

Expats in China, who had carefully built their Xiaohongshu accounts for years, were visibly upset. “We’re all foreigners, but why does one ‘nihao’ video get thousands of likes? I’ve studied Chinese for 10 years!”

Chinese netizens had a term for them: 嫡长子 (legitimate firstborn son of the empire). My boyfriend, a 嫡长子 after a decade in China, didn’t care much about the trend. His take: “Suddenly, the U.S. has a China craze?”

We bonded over the problematic word choice—“refugee.” While real refugees from the Global South struggle to survive, it felt so American, so neo-imperialist, to appropriate that term for TikTok exiles.

We vented over a particular video: an American questioning the colonizer narrative while calling Xiaohongshu “Red Note.” How introspective! It fits perfectly with the tag 洋悟运动 (“Foreigner Enlightenment Movement”), a tongue-in-cheek reference to the Qing Dynasty’s 洋务运动, which aimed to modernize China by adopting Western technology while preserving traditional Confucian values.

Perhaps the most absurd take comes from Daoist believers, saw this moment as China’s destiny. They pointed to this being the year of 离火 (Lihuo)—where red symbolizes prosperity, and the earth’s vibrations align with spirituality, embodying ancient Chinese wisdom of mind-body harmony to lead the world out of chaos.

Everything seemed to click: AI-powered translation going mainstream, the U.S. government’s TikTok ban, and China’s 10-day visa-free transit policy. This surge of interest in China felt almost preordained.

Let’s embrace the waves after waves of culture (and reverse culture) shock

We can intellectualize it all we want, but heck, it’s fun to just observe this culture clash, just how quickly everyone learns and joins the conversation:

American: “We’re asked to support the family financially after we turn 18.”

Chinese: “When your parents are old, you can pull off their oxygen mask.” (A phrase describing revenge.)

Other Chinese: “The painful truth—American parents may never even get access to an oxygen mask or a hospital.

Interestingly enough, the topic of parents came up in an aesthetic discussion:

An American user with the ID “Apple” in Chinese, a sweet-looking girl studying the language, answered the most common question about her nose ring. She explained it dates back to Indian and South American cultures from the 1900s and was later adopted by Americans. But she added, “People keep comparing me to cows. I get it—but in America, that means fat and ugly. The culture shock has been wild.”

Chinese netizens had their say: “If I got a nose ring, my mom would chase me to the field, yelling, ‘You can eat after you finish plowing two acres of land.’”

Another Chinese: “In China, the body is a gift from your parents. Only cows wear nose rings, so parents wouldn’t tolerate it.” (This led to Chinese kids sharing selfies with their own nose studs)

Sometimes, they joined in to poke fun at other countries:

Chinese: Wait, Christmas isn’t Korea’s? It’s American?

American: Koreans also claim they invented KFC—Korean Fried Chicken.

Korea: Christmas is Korea’s. Please respect that, even the Chinese know this.

Chinese: Why are there so many TikTok refugees but no Koreans or Japanese?American: Because it’s just a conversation between parents.

Take Akisa Redsolider, a creator who posts videos of fishing while speaking Dakota Sioux. Under one of his posts:

Chinese: “Thanks for your fish tax.”

Members of the Chinese Hezhe ethnic group chimed in, curious if they shared ancestral ties.

And the fun of any language newbies is to learn swear words, but here is a serious inquiry:

American: “Why does ‘cow vagina’ mean awesome in Chinese? Can someone explain?”

An account, “China Florida,” shared bizarre clips of China: a grandma playing pool with her walking stick, a flaming truck on the highway, a man cosplaying as a monitor, and a chicken dribbling a basketball.

American: “I’m from Florida. This place feels just like home.” (150k likes)

And finally, this one had me laughing out loud: An American user asked, “Why are there no ads on this app?”

Chinese: “Wow, your English is so good! What language app do you use? (Wink wink)”

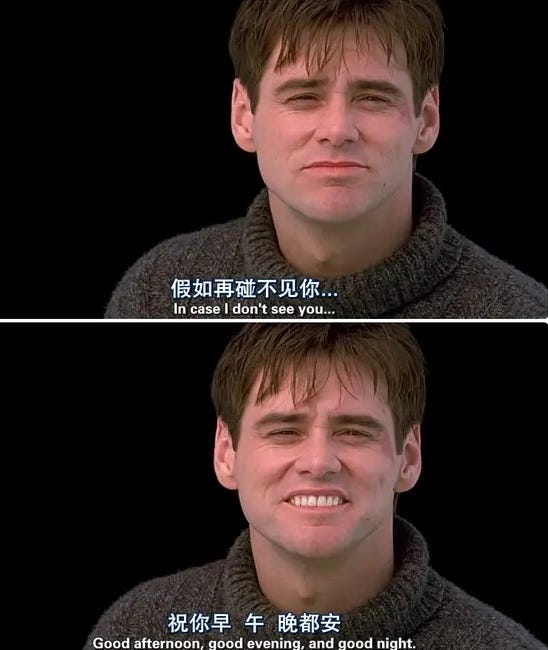

Another chimed in: “Have you seen The Truman Show? Yeah… it’s like that here.”

Chinese: “Spend enough time here, and you’ll see the ads are hidden. When you think someone’s sharing their life, it’s actually an ad. When you think someone’s complaining, that’s an ad too.”

American with username Jos: “That sounds annoying. Makes me want a cold, refreshing Bud Light.” (3,065 likes.)

Told you, everyone is learning fast.

The WALL

One Chinese blogger analyzed that the comment craze stemmed from being stuck in an echo chamber for too long—too many soft ads, too much repetitive content, and similar narratives.

So, when the TikTok refugees flooded in, for native Xiaohongshu users, it felt like falling into a rabbit hole—a kaleidoscope of new content, even sparking physical excitement, a sensation only understood by those confined within the wall.

Posts that were saved less than 10 days ago have disappeared, with content like, “This is a historical moment, as everyone is fast exchanging memes. A lot of things have changed. Not sure if the governor will allow it.” There were also posts comparing and contrasting medical bills and housing costs.

While China has an invisible wall, the U.S. tried to build a literal wall between US and Mexico—both built to divide people.

Ten days ago, Trump was inaugurated. In his speech, he outlined his vision for America, declaring the beginning of a “golden age.” His first actions? Postponing the TikTok ban—a move major media outlets called a “great marketing stunt”, withdrawing from the WHO, renaming the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of America, and recognizing only male and female genders.

The political motives behind China and the U.S. building their many walls ultimately backfired, sparking the very cultural exchange they sought to prevent. Is it history? Is it absurdity? Or is it just the internet doing what it does best—making us laugh, cringe, and question everything at once? Whether it’s through memes or mistranslations, people still find ways to connect, even when the world feels chaotic. If this is history, it’s the funny, messy, deeply human kind—and that’s worth remembering.