The Week I Replaced a Human Editor with ChatGPT

"Is this the death or the dawn of writing?" I asked journalists, editors, and institutional researchers

Part 1: ChatGPT vs. Human Editor

Over my 7 years (and still counting) as a journalist, I have had a number of editors. Since I cover the China sector in English, most of my editors have been white males. Most of the time, we make a decent duo: the native Chinese me harnesses the Weibo and WeChat’s hot buzz, and they edit intently, often with wonderful literary appreciation and somewhat intense curiosity about China.

If I had to put them into fictional boxes, like everything on the internet today, they would fit into the following categories:

The culture connoisseur wanna-be:

Someone who has never set foot in China but uses editing as a way to satisfy their curiosity. They can help build up a descriptive scene but are not very helpful for fact-checking or when asking questions like "Is it really true that people in China watch a lot of livestreams?"

The word economize wizard:

Someone who has lived in China for years and edits with ease, cutting aggressively for clarity. It's like your work has undergone a painless weight-loss surgery.

The sensational headliner:

Someone who stresses a headline over the body of the article, and being controversial is what they like the most. They might write 'evoke fear' and three exclamation points over your reporting printout. Ethical or not, sometimes you might admire their genius business mind.

The scope investigator:

Someone who was educated in traditional journalism school and loves an embargo. They always ask, "What's the scope?" and can add a flair of TMZ to business reporting.

The disciplined Mother Teresa:

Someone who says, "If you can't write it, then drop it." "Please treat the editorial calendar like the Bible." They are harsh but can inspire you intellectually and spiritually, and give you a copy of Cat Marnell's memoir, "How to Murder Your Life," as a form of encouragement.

Overall, I've learned that editors are fun people to be around but still somewhat intimidating to work with. Maybe it has to do with how intimate writing can be. The moment I send my draft to the editor via email, it still feels like I'm giving away the right for someone to fondle my underpants.

A month ago, while debating whether or not to hire an editor for my Substack, ChatGPT arrived in China after a year of making headlines around the world. Two of my friends raved about using ChatGPT at work. A journalist-turned-corporate PR used it to write news releases within minutes, saving her from days of work. Another video journalist loved brainstorming headlines with ChatGPT. It's like having your own private help behind your boss's back.

As a digital laggard, I was tempted to try it out. On a random Saturday night, plagued by my Chinglish, I opened ChatGPT3.5 and played with it until 1am. Needless to say, we had a good time.

I started running different iterations with commands like "causal tone," "more eloquent," or "stick to the original as much as possible." If the original wasn't well-written, the revisions could be weird but coherent in their own way. It's like having an editor that's free and works at the speed of lightning. After years of dreading a human editor's revisions, it's finally my turn to choose the help I want. It's truly a blessing and liberation.

Part 2: Devil's Advocate

ChatGPT has given me the confidence I never had as an ESL writer. I wonder what other journalists and editors in the China sector think about it.

My journalist friends from established foreign media are wary of ChatGPT, seeing it as a cheat or a potential information leak. A few reached out, and one friend directed me to Jeremy Goldkorn, Editor-in-Chief of The China Project (formerly known as SupChina) because he seemed very "anti-GPT."

In our conversation, he corrected me that he doesn't have a problem with using ChatGPT, but as the head of a publication, he is not going to publish articles written by it or use images created by AI. He explained that it's his job as the editor to build trust between the reader and the journalist. When he doesn't trust AI enough, it's impossible to foster the desire to use it.

Nevertheless, technology will keep getting better, and it's just a matter of time before we learn how to use it better (kind of like journalists learning how to Google; quite an interesting example he gave). And of course, the cost of content will decrease even more.

Although Jeremy has also experimented a lot with creating China-related AI images, to his disappointment, they are all orientalist clichés.

AI can only make art based on what it has been fed, which are the human-created photo. Jeremy argued that if we keep using it, we may turn into this weird, inward-looking cycle: "It does not move our culture forward but backward. And it's our job to help people think beyond the clichés."

Ted Chiang would agree as well (I bookmarked his New Yorker piece during the ChatGPT news boom, and his concept didn't click with me until now). He projected a generation of blurry writers:

"Can large language models help humans with the creation of original writing?...If you're a writer, you will write a lot of unoriginal work before you write something original. And the time and effort expended on that unoriginal work isn't wasted; on the contrary, I would suggest that it is precisely what enables you to eventually create something original.

The hours spent choosing the right words and rearranging sentences to better follow one another are what teach you how meaning is conveyed by prose. Having students write essays isn't merely a way to test their grasp of the material; it gives them experience in articulating their thoughts. If students never have to write essays that we have all read before, they will never gain the skills needed to write something that we have never read."

Amen! I am all for hard-earned human creative expression, but I want to try it out myself.

Part3. ChatGPT as A Creative Writing Partner

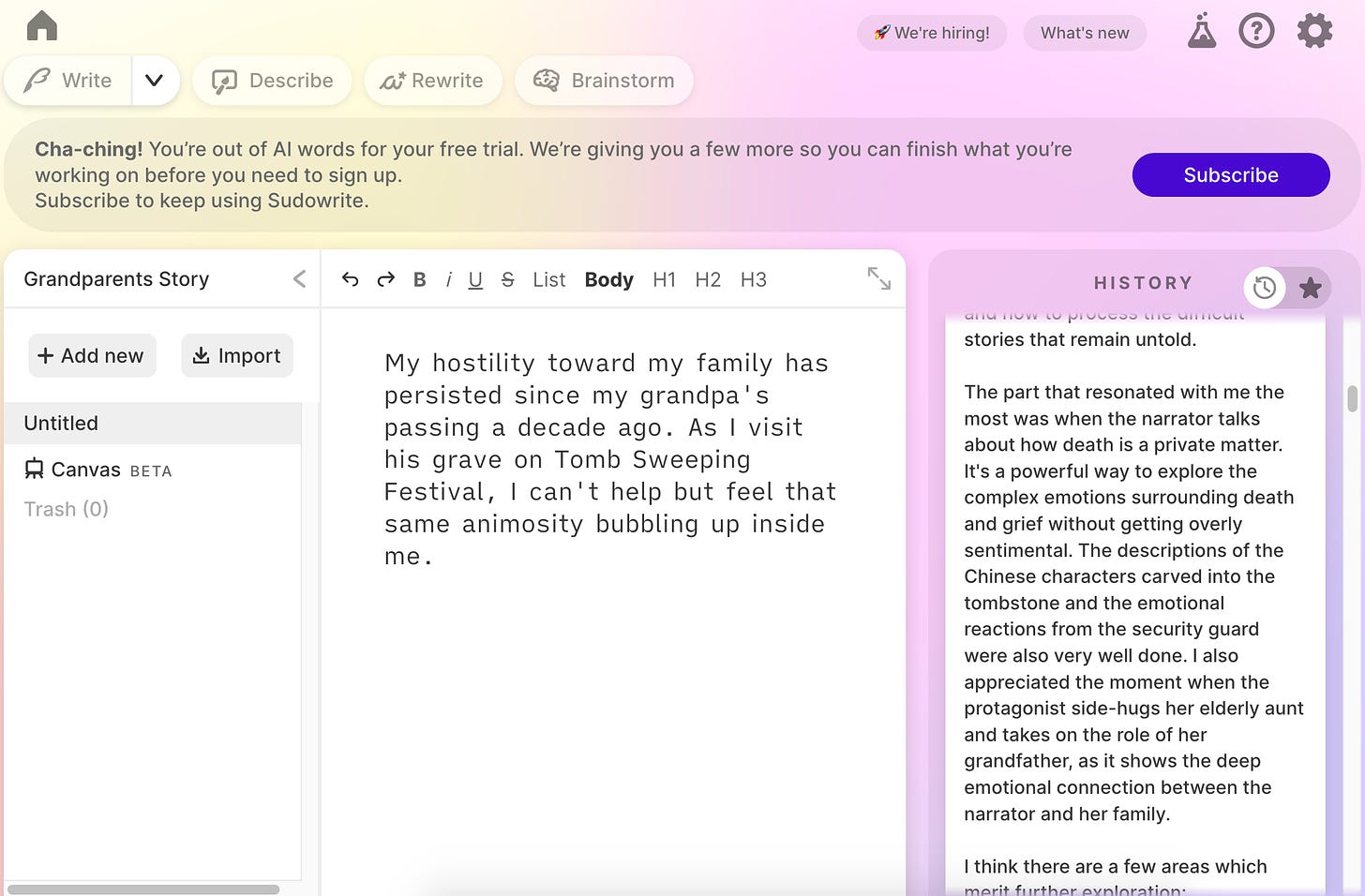

I decided to put my other creative work to the test: a personal essay about visiting my grandpa's tomb with my parents that I had been working on frustratedly for over a year. I saw the flaws: the lack of scene descriptions, suspense, and logic. I was all over the place and desperately looking for reader feedback. As I used ChatGPT for a grammar check, I was reminded of how it could also provide feedback.

The next week, I happened to be in a writing workshop for the NYTimes' Modern Love column, and the feedback I received from my fellow writers was almost identical to ChatGPT's - yes, more personal and somewhat unexpected, but still, ChatGPT opened a new tunnel for me. It was like a gentle writing partner that guided me with its hand to see the vast possibilities of my words and stories. Cutting off the busy work of going back and forth with an editor, it invited fun and inspiration back into my revision process.

Out of curiosity, I typed the command, "So, how could you revise it following your own advice?"

The results were mixed. While I could never write elegant and vivid sentences like "I can't help but feel the same animosity bubbling up inside me," beautiful metaphors aside, the revision omitted a lot of details, ignored my self-deprecating humor, and got rid of necessary cultural background that I had carefully planted. ChatGPT had turned my words into a standard personal essay with not much flavor.

So I then went on to explore other AI tools tailored towards writers out there. I tried out Sudowrite; it was built similarly to a Google Doc template and had buttons on top to explore options to advance your creative writing: expand this to four senses, rewrite to change POVs, more inner conflict, etc. The feedback was amazing, more comprehensive, and offered different POVs, up to three feedbacks with 500 words each. You could sense that the machine was really reading your work. But overall, the usage was less intuitive than the chatbox on ChatGPT, and I found that it somewhat disrupted the writing flow with all those fancy options.

A fitful in-between tool is Notion. It operates more like an old-fashioned editor, editing sentences by sentences, not as busy and literary as Sudowrite, but less intelligent and free like ChatGPT.

Both Sudowrite and Notion offer the option of auto-generate, basically picking up where you left off and continuing to write. It's fun to see the road they head in, mostly predictable and somewhat cheesy. But both run on a subscription model, so when you hit the usage threshold (usually after a few hours of playing), they ask you to pay. Unlike ChatGPT, the free version hits almost no limit.

Here are a few lessons I have learned from testing it out myself:

You MUST have creative control of your own story and not be overwhelmed by the opportunities of plot options the AI is offering you.

AI is a wonderful writing partner. It walks through your old pieces and can ignite new ways of writing, particularly useful for old dusty files that you're in the mood to give another chance.

A creative writing professor once offered this advice: "AI can produce a good essay, not a great one." Predictable but pretty true.

But after weeks of experimenting, the (sad?) truth is that I can't imagine writing without my ChatGPT.

Part4. CHINA!!

The only hurdle I encountered was when trying to translate an English interview transcript to Chinese. The result was as disappointing as Google Translate's. It left me confused. While the Chinese to English translation works amazingly, with perfect language and composition, the output in Chinese may not be ChatGPT's strength. This may be because English is its primary language, sourced from all English content, academic papers, and Google content.

But it's not like Baidu's Ernie Bot文心一言 was an equal substitution, for apparent reasons (pre-recorded product launch flop, suspicion on the base code belonging to OpenAI, etc.).

I felt stuck. Along the way, Jeremy raised an interesting topic: AI is a tool that lies at the intersection of technology and content. As much as China trumps in technology (ex: WeChat), it lacks content. Why? Censorship. "How does censorship affect the output and performance of AI?" he asked. "What's the cost of not progressing in this type of territory?" I followed.

I felt like we were onto something here. Luckily, a friend introduced me to a researcher who has knowledge of how people in local cultural institutions approach ChatGPT. Let's call him Mr. M. His answers were not so positive, even depressing.

At a recent gathering he attended, some of the established scholars from the last generation in China were overjoyed because they could now use ChatGPT to write official papers. But on second thought, Mr. M questioned the bureaucracy of it: "When we are using machines to cheat, wouldn't it be nice to drop the orthodoxy altogether at once?"

"What's more scary is not that machines substitute humans, but once machines are applied, there is no limit to such bureaucracy. In the past, however, the government pushed individuals to write, there was only so much they could write. But suddenly, the power of labels is liberated, and there is no ceiling to such bureaucracy."

Mr. M observed that the application of AI has expanded beyond writing paperwork to smart spot censorship—not just based on literary meaning, but interpretation of the overall meaning of documents.

Mr. M held quite a cynical view. Our conversation did latch onto other topics like how few artists actually integrate their philosophy with AI work, but rather make statement pieces—the process of creating a work is less important than when to publish it, which runs pretty much like a news piece. Mr. M is a firm believer in learning the process, and some processes can't be skipped with AI. But then again, we are powerless in front of tech evolution and retreated back to our observer role.

If you want to understand more about ChatGPT in China, censorship, and the battle against the US, two bumingbai podcasts (in Mandarin) are probably the most comprehensive content out there:

EP-037 Tinyfool:How ChatGPT Will Change Our Life?

EP-036 Xu Chenggang:Looking at China and the United States AI Battle Through ChatGPT

After a week of experiment, I am positive about having ChatGPT as my line editor since it is a natural language processor. However, I am less confident about using it to substitute the creative process. I guess both people I talked to would agree as well: Process matters! And it gives the unexpected sparks to creating things! Maybe the shortcut from ChatGPT hinders our authentic creative brain that comes naturally to us humans. Although abandoning it won't help, we need to learn how to make it our best friend.

PS. I realize that this issue is a bit late to the trend, but ChatGPT is really a paradigm-shifting technology, and I would like to keep my eye on it, especially on how artists are using it and creative prompts in different fields. Contact me if there are certain relevant topics you are interested in, as I would love to look into them as well.

Special thanks to Yaling Jiang for her contribution. Check out her Substack next door for a fresh slice of Chinese consumerism: Following the yuan.

Thanks Anthony for the introduction. Be sure to check out his Substack Poetry from Beijing for a soulful and lively glimpse into China.

And thanks Wency, Toby and Luna for being my unsolicited editors :)

i'd be really interested in hearing more bout the use of LLMs to automate censorship by viewpoint that Mr M mentions