Navigating a confusing time in Post-COVID China has lead me to interview these artists

Could the way we remember the past change the future?

I hate leaving things unsaid, especially when it comes to finding closure. I'll admit, I've been known to fast-forward to the ending of a book or read reviews before watching a movie. When I go through a breakup, friendship or relationship, I pour out all my feelings in long letters and try to mend any broken bonds. I believe that by putting everything on the table, we can move on and improve ourselves. But for what has happened in the past three years, my head has been in the clouds and I've struggled to find the proper closure I crave.

During my recent visit to Shanghai, I couldn't help but feel overwhelmed by the city's renewed vibrancy that caught me off guard. Everything had changed overnight, and the experience was surreal. The experience of walking unmasked and entering stores without having to scan a health code filled me with newfound appreciation for the smallest pleasures of life. It was intriguing to note the extent to which I had grown accustomed to the pandemic's previously mandatory precautions, which were now deemed obsolete.

Just a few months ago, people on WeChat Moments were fighting over viral protest videos and trying to understand differing opinions. Now, it's the brunch seating that we're taking a stand for. Sadly, human nature's fight for resources continues.

At an intimate house party, one thoughtful observer noted a collective fragility still looming, which another agreed with. People have been retreating both physically and spiritually in the past few years, making them resistant about opening up. Perhaps, this will be the defining theme of 2023.

I want to understand, but the past seems to slip away from our conversations. Therefore, for the very first issue of TCK, I have decided to feature three artists doing exemplary work to commemorate our old wounds.

Pt.1 Mr. M - Filmmaker - The Shanghai Ghetto

A filmmaker who experienced the quarantine in Shanghai makes a resounding denouncement.

After much media spotlight on his work, this artist wishes to remain anonymous in this issue, and asked to refer his latest 30 minutes movie as The Shanghai Ghetto. So I took the liberty to call him Mr. M.

I first read about his work during a chaotic time in Shanghai. In this short video, he performed a little treat or trick gimmick from the outside of his window — he sat up a speaker blasted out random propaganda generated via AI, and fooled everyone including his neighbors and big whites. He also did a series of photo shoot, posing the Chinese cough medicine (莲花清瘟 a traditional Chinese medicine formulation used for the treatment of influenza) as the subject, framing medicine in bagel toasters, microwave and heated stove. His work is creative, ironic with a hint of humor.

For the first half year of quarantine, Mr.M was almost jobless given the bleak film industry, earned 500 RMB from a gig. He also experienced a burst of creativity and worked on making The Shanghai Ghetto.

Narrated in Chongqing dialect, the tone of the film is very engaged in voyeurism, like turning on a late night TV show, or someone is spying through the peephole. Most of film happened side of his window — his only source of outside besides his phone. Two key events happened (SPOILER BLOCKER) to symbolize people’s fight against the system. He also creatively included footage from other people’s short video in order to narrate the whole picture of those events.

Contrary to the somewhat barbaric scene in the film, our conversation remained in a civil manner. Like his film, his calm words was like a surgeon’s knife, cut directly into the heart of the problem (his answer were translated into English here):

Do you feel like the city has moved on with no regard of the past?

I think it's very likely that it's as you said. On the one hand, the ideology of Shanghai city is like that of ‘Myth of Love(爱情神话),’ living in fantasy and scenery that is fake to an extreme. For Shanghai people, personal daily life is a top priority, and anyone who takes that away will be severely punished, but they are not concerned if others' are taken away. On the other hand, everyone really has no way to show anything, has long been accustomed to silence, and there is no space for discussion. I'm afraid it's the same all over the country. At least the young people in Shanghai had some influence at the end of last year, shouting out something that loosened the entire epidemic prevention policy. This is also a progressive side of Shanghai. There have always been these two sides in Shanghai: self-preservation and progressivism. It was the same during the period of being isolated. Then, the next will be the dispersal period.

So how exactly do we live forward?

There is no accountability mechanism, and those who speak the truth are suppressed, and the masses who can unite are being dissolved. In the end, they fooled themselves, left with no solutions. Even if this kind of trauma is not forgotten, the object of the contradiction will continue to shift in the rewriting of memory, and finally fall on something. The cultural system of this place is like this, very strong and stable."

Thank you Mr.M!

Pt.2 Zou Xue Ping - Documentary Filmmaker - The Village Series

For a decade, a documentary filmmaker traced the memories of elders in her home village, starting with the Great Famine

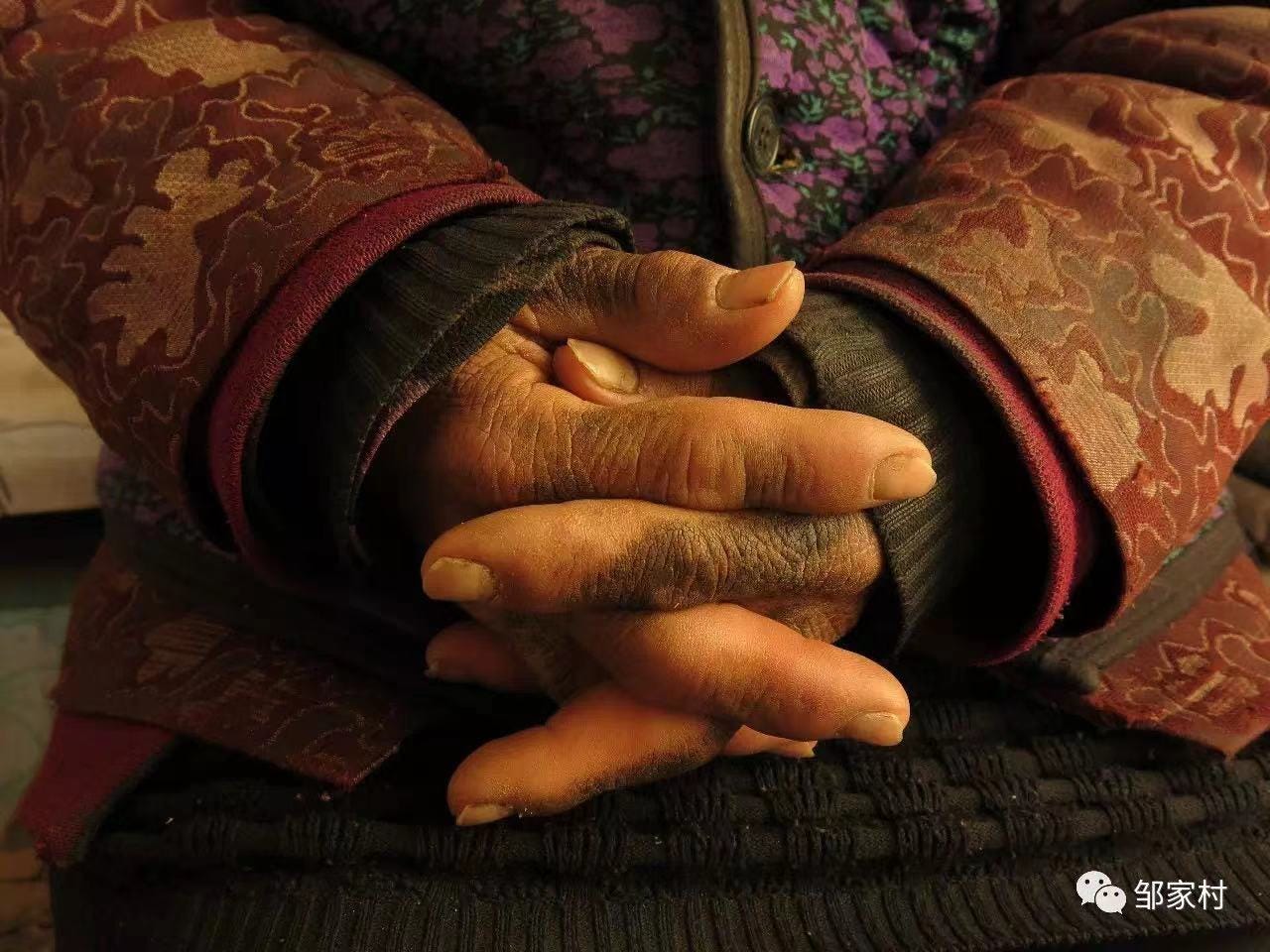

People from her hometown view Zou as an idiot. She grew up in a rural part of Shangdong province and went to China Academy of Art, where she took a documentary class by chance. After graduation, she started to film buried village histories, particularly the Great Famine in the 1970s. This became the basis for her ten-year-long series on the village.

Her idiocy stemmed from her persistence and initiation on unearthing the past. Villagers responded with "What's the use?" and her parents resisted. Her first documentary screening of The Hungry Village in the village prompted intense reactions, like a pebble disturbed a peaceful lake surface.

What fascinated me was Zou's approach of working to create an ecosystem. She used five films to complete her famine series and accomplished a list of items including and not limited to: recorded elders' memory, filmed people’s reactions of watch it, instructed the children to interview elders, and crowdsourced to build a monument.

Slowly, past sorrows descended; all that remained was the power of choice to remember through a camera, lighthearted and filtered through children's eyes.

Zou struck me not just as a documentary filmmaker but also as a historian. Her WeChat account consisted of hundreds of posts, an archive of her shooting diaries, her gentle words never scaring followers with her ambitions. Over the past few years, she sculpted her village and characters from vague, black and white objects into a universe filled with humane, complex, ever-growing characters.

Now, most of the elderly have passed on, and many youngsters relocated to cities. This fact led Zou to start contemplating their relationship with the village and prompted her a possible new documentary idea.

I wondered if Zou ever pieced together the great famine history and if recognizing the past had influenced her vision of the future.

Is it part of your DNA to document missing histories?

Ten years ago, I began filming my family and collecting their and the village’s memories, later I incorporated teaching the children there to use the camera as well.

In October of last year, I took some children with me to film the Shanghai Confucian Temple. Upon returning to the temple in February, I was struck by the significant changes that had occurred and the large number of people who had since departed. My curiosity was sparked, and I began to investigate the state of old communities and historic structures in Shanghai. I believe in the adage "no past, no future." If we do not make an effort to understand our past, how can we ever hope to move forward in life and society? Thus, exploring the historical context of our environment is essential to knowing what the future might hold.

Many of the children I work with come from privileged backgrounds and have rarely been exposed to the living conditions of others in Shanghai, which can be crowded and unclean. This is a new reality for them. Their parents remind them that if they do not apply themselves, they could end up living in similar conditions.

Your film was been shown to different kind of audiences throughout the years, were you surprised by their reactions? Did their reactions change your memories of the Great Famine?

When showing the film to both children and older generations, the latter often wished to discuss history but were hesitant to speak openly to outsiders and risk ridicule. This reluctance, despite the passing of 50 or 60 years since the Great Famine, may be attributed to traditional influences, such as the Chinese saying 家丑不可外扬 (which translates to “Family problems should not be publicized").

When interviewing them, I discovered that they had endured significant hardship in the past and feared retribution, such as being 批斗 (which translates to "criticized and denounced publicly") during the Cultural Revolution. Consequently, they remained unsure about whether or not they could speak freely. They often leave a lasting impression on their children and shape their view of society. So compare to the actual history event, I was intrigued by their attitudes towards history and how they were able to perpetuate their way of thinking.

Do you think changing the way we think about the past could alter our future?

If we talk about myself, for example, there is a big contrast between before and after going to college. Before, I was a very obedient child, but after graduating from college and going to Hangzhou, a new first-tier city, my environment and lifestyle gradually changed. Later, when I went to Beijing’s Cao Changdi, that experience altered some of my views on society and the future path I choose to pursue.

At that time, recording this history was slowly changing my way of life. By filming this footage and making it known to more people, I was then able to make the second, third films, and could focus on this direction. I don't think it changes how I perceived the past memory necessarily, but for me, these experiences have given me the strength to go back to the path of documenting film.

For example, recently I have been editing and organizing my aunt's materials. She has passed away, and it's not like I have a lot of footage of her life, only within the last five or six years it was slowly put into my video. Now, when I look back at this footage, I realize that my aunt was a very impressive woman, she had a forward-thinking and independent perspective on many things, including important events in the country or experiences of leaders, as well as against early-marrying and early-childbearing.

Do you think your aunt's independent thinking was innate or influenced by something else?

Firstly, she was isolated in the village and in her family, and gradually formed her independent thinking in this state of isolation, but it was unconscious, and no one talked with her about it. I think she had a natural curiosity about people and things that she encountered.

What’s your dream project regardless of time and money?

Actually, I'm preparing to make a film including all the deceased people, and Yuqian’s father, another uncle who suddenly passed away, etc. I want to tell their stories. They passed away very early and have slowly been forgotten. This film can be shown to young people in the village who don't know much about then.

I also wanted to build a public space in the village where I could show my documentary, photos, the village genealogy, a center to archive these stories. It would be an open space where everyone can gather and collect some historic artifacts from the village here.

As a continuation of her documentary, Zou has created a documentary camp to teach teens above the age of ten. If you're interested, please contact her via zouxueping1985@126.com for more information. The world needs another young Zou.

Pt.3 Toby - Indie Game Maker - Superstitions

A video game developer attempts to reimagine the generational consequences of China's One-Child Policy.

I am forever admiring Toby’s calm and quirky personality and unexpected humor. I’m proud to have seen him finish the demo of his game project, Superstitions, which is an open world RPG set in rural China.

Toby keeps me informed about current events, such as the Japanese scholar who suggested elders commit suicide, the Ohio train derailment, and local Chinese politics. He often speaks critically but gently about Chinese policy.

Superstitions demonstrated this. It presented a Chinese struggle — questioning the weight of individual sacrifices over the greater good. Toby started the game with a film-like script, where the lives of several characters entangled together to reveal a cross-generational drama resulting from the enforced One Child Policy.

I was immersed in the scene right away, sounds of ambient village noise and pixel art that reminded me of the good old Gameboy era. My personal favourite part is seeing Mao’s profile frame right in the character’s living room.

It becomes clear fairly quickly in the game that the main character suffers from Kleptomania, a mental health disorder where one steals things they don't necessarily need. His toolkit helps unravel the clues leading to a murder at a Taoist temple. (SPOILER) A female cult group is ultimately involved.

Toby graduated from the prestigious Wesleyan Liberal Arts School, where he studied cinema and computer science, blending his artistic taste with his analytical mind. He was recently admitted to NYU game center, his top choice. Hope Toby will continue making rock games!

So what prompted the One Child Policy discussion?

When I started writing the script for the game, I wasn't really thinking about any historical policies. I was more interested in creating a crime story with a Chinese setting. Although, there was one point when I considered including a cult member killing a Taoist priest, inspired by a news story I'd read. But I ended up dropping that idea because it felt too fictional.

The One Child Policy actually came up in a random conversation with my mom. She told me about seeing a pregnant woman from a rural area being forced to have an abortion, which made me think about extreme measures like those that cults might use. I created the game to explore the potential consequences of such policies. But I don't think that the One Child Policy is the only focus of the game. And there's no clear-cut good or bad in this situation.

Just like in our daily lives, events from the past can slip into our memories, but they're not the only things that define us. The game is a blend of various themes and ideas that touch upon the complex experiences of people living in China.

How were you able to fill in the gap between the game and the reality?

I wanted to make the game as true to life as possible, so I decided to set it at a Taoist temple where the local women pray to GuanYin for fertility. The ironic thing is that the actual situation was probably even crazier than what I could come up with in the game. People in rural China are often superstitious, and I feel like this situation really captures that. I imagined that most people who witnessed what was happening would stay silent or not take action. That's why the ending of the game is about seeking a kind of personal revenge.

However ambiguous you tried to write the story, I feel like I took the side of the cult women more when reading the script.

I think that there's no clear-cut good or bad in this situation. That's why I made the person in charge of family planning a woman with a child with disabilities. Despite her own desire for a second child, she's the one who has to enforce the abortion policy. I think deep down she believes that this is what's best for everyone in the bigger picture, even though it's a difficult position for her as a parent.

What’s your personal opinion on it?

I get why the policy was put in place, but I have pretty mixed feelings about it. The biggest issue for me is how it's enforced and the negative impact that can have on families. I mean, rewards for not having more kids make sense as positive incentives, but it's hard to ignore how traumatic it can be for someone to be forced into that decision.

We then latched onto a conversation about an alternative reality if the policy wasn’t enforced and whether or not it will continue to deepen the gender imbalance…(save 500 words here)

Who are you hoping to play this game?

The professor at admission offices for my graduate school application (laugh) or my privileged, baizuo (Western leftist) friends like you. But ultimately, I really want Chinese people to play it and reflect on their own country.

Do you wish to make more culturally-relevant games?

Personally, I wish to make games that closely relate to real life or even project us into the future. Reading Ted Chiang’s short story "Liking What You See: A Documentary" recently gave me a revelation. The story debates the pros and cons of a new technology called calliagnosia that allows people to switch off their ability to perceive physical attractiveness. You can still tell if they're happy or sad, but not cute or ugly. Some argue that this will eliminate discrimination and create a more equal society, while others believe that it will end up leading to more societal divisions and the removal of beauty as a concept. Essentially, the takeaway from the story for me is that we should reject appearance-based discrimination rather than trying to change how we perceive appearances.

What’s something so polarizing about US and China that you have a hard time to place yourself?

My cultural identity is a lot like a spectrum – kinda like how the Kinsey scale works. Sometimes I feel more in tune with American culture, other times I feel more connected to my Chinese roots. But at the end of the day, I feel like I'm my own independent person. Although, you could say that valuing independence is a very American thing."

Thank you Toby! You can find him via jliu9963@gmail.com

.

.

.

The works of three artists are inspired by real-life events that are difficult to look back at, yet their evocative and varied approaches express their feelings about history in poignant, ironic, empathetic, and sometimes humorous ways. Mr.M prioritizes preserving memory and understanding the whole picture, while Zou focuses on revealing the invisible scars left on survivors, and their impact on future generations. Toby takes creative liberties by imagining opposing groups' intentions and perspectives, creating a fictionalized history with an open ending.

Putting the artists' work and thoughts under a microscope, I searched for a perfect formula to mend physical and emotional scars caused by the past. However, I question if closure is always necessary, and how much we can change the future by altering the past. I am uncertain how much healing China can undergo, at least those artists reminds us there is meaning to remember.

For more commemorate post about China in the COVID era, here are a few resources for you to understand:

Mr. M's recommended an art exhibition showcases traditional artists' paintings documenting the day-to-day life during the COVID-19 pandemic. On display until April 14th in Shanghai.

Sandwich China posts (in Chinese) for Shanghai quarantine first account diaries

Follow those Instagram account for COVID-19 China Memes (in Chinese): richkids_english_police & bayareashitpeople_

If you've made it this far, I'd love to hear from you in the comments!

Thanks Wency and Tianpei for being my most faithful reader, Xiaoxue for the best cheerleader, Luna for being the unpaid editor, Siyuan for the inspo, and Toby for being such a muse as always. Thanks ChatGPT3.5 for editing. Until next time.

hey! is this only way to access these works to cold email the creators? (/is it worth doing so, i.e. are they willing to share with friendly strangers?) even the few links in the post seem to be broken.