language itself is not misogynistic

A feminist guide to take back language

Since starting my new job, I’ve noticed a strong focus on language. At the fashion publication, it’s not just about vocabulary—it’s about how we talk about fashion and the specific words we choose. Fashion is tied to culture, and culture to language, which often reveals deeper subconscious patterns. For example, a literary-savvy businessperson can use precise language to shape a brand’s narrative, identify pain points, and build trust.

Here’s an article I edited recently, featuring Amanda Montell and her book Wordslut (click here for original post). Interestingly, the writer I worked with for this piece had also written her undergraduate thesis on the femaleness of foul language, around the same time Amanda published her book. During our video interview—me in New York, the writer in Mexico, and Amanda in LA—Amanda bursted out laughing when we debated whether shifting from “oh my god” to “oh my goddess” could alter our subconscious perceptions. It made me rethink using phrases like “fuck your mother (操你妈)” in arguments, realizing that any insult involving “mom” inevitably brings up thoughts of my own mother. Would I really want to associate her with such language?

Does this awareness empower us, or can it be weaponized against us? Does discussing these ideas in a book versus a public forum signal progress? I don’t have clear answers, and the questions continue to linger.

Meanwhile, the recent success of the film Her Story (好东西) at the Chinese box office suggests feminism is making tangible strides. The film raises important questions: How would a feminist handle a situationship? How do they educate their daughters? How does feminism influence everyday conversations? Feminism seems to be weaving itself more into our daily realities—at least in China.

Read more about Amanda Montell and Wordslut here:

Language Itself Is Not Misogynistic

Written by: Chen Huang

Amanda Montell, now 32 years old, is not a “scholar” in the traditional sense. She has authored three books on linguistics and sociology, yet her writing lacks the usual academic dryness. Instead, her work is filled with traces of pop culture—likely influenced by her time as a beauty editor after graduating college. During that period, she published her first book, Wordslut (2019), a work that reimagines language through the eyes of a 28-year-old woman in Los Angeles.

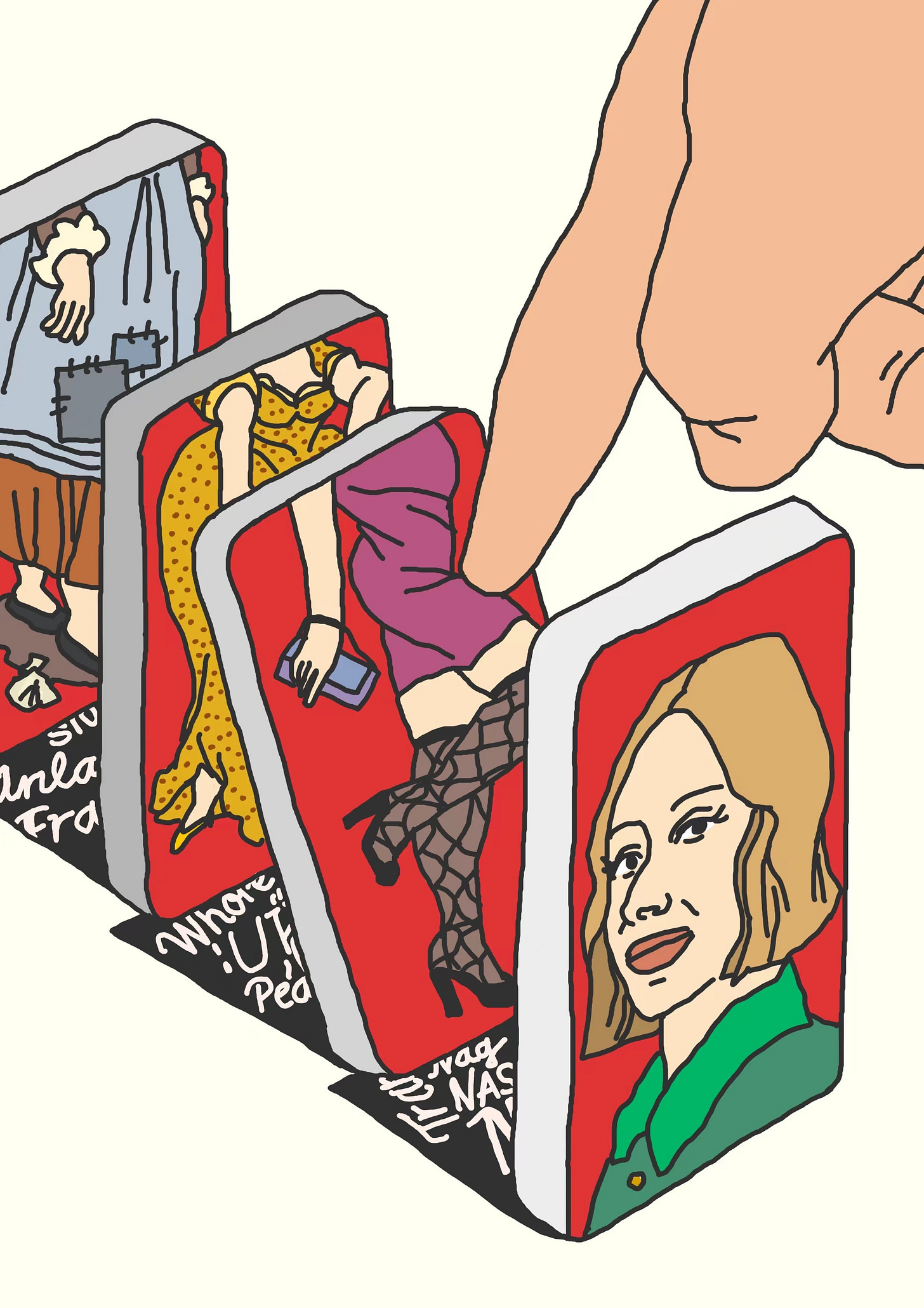

Wordslut can be considered a popular feminist linguistic guide—a manual that transforms obscure academic theories into practical, everyday applications. It unpacks English terms used to demean women—such as "slut," "bitch," "sissy," and "pussy"—and explores how these once-neutral words gradually became pejorative. Correspondingly, Montell examines how male-oriented or masculine-coded language is often seen as inherently positive. Through feminist linguistic waves, scholars have demonstrated that patriarchy infiltrates every aspect of daily life, shaping behaviors and controlling our lives in deeply embedded ways.

Montell prefers to call herself a writer or journalist rather than a scholar. What she truly wants to explore is how humans think, connect, and assign meaning to everything in life—and linguistics was the first tool she learned to approach these questions. With 71,000 followers on Instagram and a pace of publishing roughly one book every three years, Montell has attracted a group of like-minded followers who are “vibrant, curious, a bit nerdy, but open-minded.” To build a cohesive intellectual universe, she transforms sentences from her books into shareable posts: “In the hands of bad people, language can be used as a weapon. In the hands of good people, it can change the world.”

Montell is skilled at writing with humor and translating complex linguistic evolution and academic theory into accessible narratives, making feminist linguistics available to more people. Four years after publishing Wordslut, Montell notes that more young women are becoming aware of gender inequalities in their everyday lives and are eager to understand how these issues arise and how to change them. Wordslut provides just such insights, as indicated by its English subtitle: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English Language.

The same dynamic is unfolding in China. Feminism is urging people to consciously avoid misogynistic language, even initiating reclamation and counteractions. For instance, “dad” has become a slang term to replace “mansplaining.” However, debates still rage over how to define and address “misogynistic terms.” Reflecting on the gender bias embedded in everyday language has largely been a grassroots phenomenon in China. Studies on the intersection of language and gender—especially regarding the gendered nature of vulgar language—remain insufficient. Should we reclaim and repurpose all gender-biased words? How should we respond to gendered verbal attacks? These are questions that require further exploration. Against this backdrop, the publication of the Chinese edition of Wordslut seems particularly timely.

Feminist linguistics has a decades-long history in the West, dating back to the 1960s when scholars first differentiated between “sex” and “gender.” This field has since inspired a global wave of thought, including in China, where the movement to deconstruct gendered language continues to grow. Montell emphasizes that language itself is not misogynistic—rather, it’s the way people use it that reflects misogyny. Just as culture shapes language use, language can, in turn, influence culture. This means we can reclaim and even alter misogynistic elements in language.

For Montell, reclaiming language is a form of everyday politics—a way to restore women’s agency.

Montell believes language wields enormous power, reflecting societal and cultural changes while reinforcing social power structures. For women and gender-diverse groups, language is a critical tool for empowerment. One of her motivations for writing this book was to equip readers with tools to make more conscious linguistic choices. She notes that young women are often language innovators, and linguistic solidarity becomes a convenient and effective weapon for social change.

We conducted a video interview with Montell. Below are our conversation:

Q: When you published your first book, you were still a beauty editor and a young woman without a strong academic background. What challenges did you face during the writing process, and how did you overcome them?

Montell: I wanted to combine feminist linguistics with pop culture. Many books on linguistics are written by scholars and Ph.D. holders, but they’re too hard to understand, right? As someone with a linguistics degree who also understands this field and writes for the internet, I had the advantage of making these important and fascinating topics accessible to those who don’t typically read academic papers.

Since Wordslut was published, every linguist I’ve met has recognized that everyone has their space and audience.

Rather than entering academia, I prefer creating nonfiction works and journalism—though the book’s themes are still rooted in social science. That said, being a relatively young woman did invite more criticism. Many male journalists write about fields like physics or microbiology, but no one questions why they don’t have a Ph.D.

Q: Your book discusses “reclaiming and repurposing” derogatory terms for women. In China, some feminists have chosen to substitute male-centric or female-centric terms with gender-neutral ones—like replacing “dick” with “stem” or “godfather” with “godmilk.” What do you think of this approach? Could it gain widespread adoption?

Montell: Linguistic change comes from grassroots efforts. For such changes to persist, broader cultural acceptance is necessary. I find it hard to imagine words like “stem” becoming widely popular. Linguistically speaking, slang gains traction when it fills a lexical gap—when there’s no existing word for a concept. For instance, terms like "fly" and "lit" only enjoyed fleeting popularity because we already have "cool." For “stem” to become mainstream, it would need a unique meaning that resonates with cultural and gender attitudes.

Q: In your book, you describe insider slang among marginalized groups as a form of identity expression. When this slang spreads online and becomes mainstream, does it risk cultural appropriation?

Linguist Sonja Lanehart taught me that you can’t stop privileged groups from using marginalized groups’ slang.

Montell: What’s important is recognizing and supporting the communities that created it. Many drag slang terms were once niche jargon but are now widely used by young people online and in daily life. This is a double-edged sword. While normalizing drag culture increases acceptance of queer communities, it also raises appropriation concerns. For instance, people who use drag slang yet vote for anti-trans policies are hypocritical. However, I doubt conservative parents even realize these slangs’ origins, and their kids likely don’t either—they’re just picking up terms on TikTok. Misusing marginalized groups’ language while continuing to oppress them only further marginalizes these communities.

Q: You emphasize the intersection of language and gender, but how do language and social class intersect?

Montell: In the U.S., the most linguistically innovative communities have historically been queer people of color. Language change is indeed bottom-up, not top-down. Academic methods of language innovation often fail to gain widespread acceptance. Some people criticize gender-inclusive language using elitist arguments, claiming that singular "they" violates “standard” grammar. But the truth is, English grammar has always evolved. For example, the second-person pronoun “you” was originally plural, while “thou” was singular.

Driving language change isn’t the domain of the highly educated—it’s quite the opposite.

Q: Why does linguistic change, unlike many other societal changes, often originate from the grassroots rather than being imposed top-down?

Montell: Children don’t decide how to speak based on dictionaries or school teachings, right? They learn language on TikTok, they invent it, experience it in real life, and innovate it within small communities. Lexicographers reflect this reality. Even if they’re taught proper grammar in school, people still speak in their own way or code-switch depending on the context. Sociolinguists believe language development isn’t driven by prescriptive rules from grammarians or dictionaries—it evolves through grassroots usage.

Q: Women are often seen as the primary bearers of emotional labor. How does emotional labor manifest in women’s speech patterns? What impact does it have on women in conversations?

Montell: Women are often perceived as “naturally” empathetic and emotionally attuned—skills honed through years of practice from a young age. This conditioning makes them genuinely more empathetic and nurturing. In conversations, this often translates to the use of filler words or interjections (“mm-hmm,” “yes, girl,” “oh my gosh,” “exactly”) to show they are actively listening. This is how they signal engagement in their friend’s story.

Q: In China, many feminists oppose using fillers like “I think” or “it seems,” arguing that these words make women appear less confident in professional settings. What’s your perspective on this?

Montell: In my work, I try to balance authenticity with speaking in ways that patriarchal systems perceive as authoritative. In real-life conversations, even in formal contexts, you’ll hear me use fillers. They make me sound authentic and trustworthy. I find that people don’t overly criticize these in natural dialogue. However, when recording a podcast, I do consciously reduce fillers to make my speech sound more formal.

Still, people critique me in gendered ways—saying my views shouldn’t be taken seriously because I laugh too much or seem too lighthearted when discussing serious topics. Ironically, my success comes not from rigid, formal speech but from speaking authentically.

A few years ago in the U.S., articles encouraged women to stop saying “like” or using vocal fry. These were faux-feminist recommendations, akin to Sheryl Sandberg’s “Lean In” approach, advising women to conform to male standards of authority. I find this problematic. While I understand that women navigating male-dominated fields may have to adapt, this isn’t feminist practice—it’s survival practice.

Avoiding phrases like “I think” isn’t feminist advice; it’s advice on surviving in a patriarchal system.

Q: Against the backdrop of rising global conservatism, what concrete suggestions do you have for women to turn language into their weapon?

Montell: We cannot underestimate the power of language. It is free and has the real ability to shape the world. Personally, I rely heavily on empirical research from linguists to demonstrate that women, queer people, and people of color deserve positions of authority and innovation, while the voices of white male authority should be challenged at every level.